Anselm's Ontological Argument

Summary

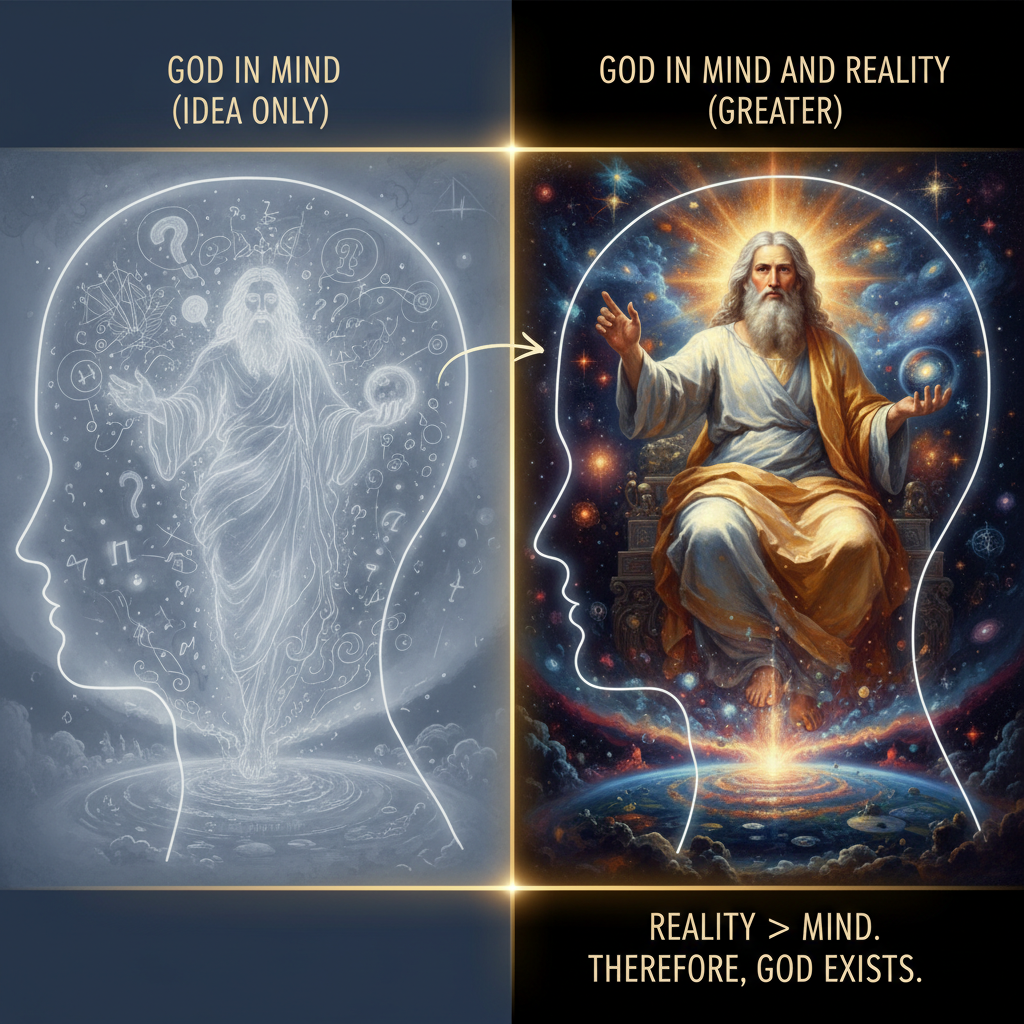

Anselm argues that God must exist based purely on logic and reason—not by observing the world. He defines God as "that than which nothing greater can be conceived" (the greatest possible being). If God existed only in your mind (as an idea) but not in reality, then you could conceive of something even greater—a God that actually exists in reality. But this is absurd, because by definition God is the greatest conceivable being, so nothing greater can be conceived. Therefore, God must exist in both mind AND reality. It's an a priori argument—it doesn't need any observations about the world, just the concept of God itself.

Detailed Explanation

Who Was St. Anselm?

- St. Anselm (1033-1109) was an 11th-century theologian who served as Archbishop of Canterbury

- He wrote his famous argument in a work called the Proslogion ("A Discourse"), completed in 1078

- The Proslogion is written as a prayer addressed to God—Anselm is trying to understand God more deeply as a believer

- His ontological argument appears in Chapter 2 of the Proslogion and is developed further in Chapter 3

The Core Definition: "That Than Which Nothing Greater Can Be Conceived"

Anselm begins with a definition of God rather than observations about the world:

God = "a being than which nothing greater can be conceived"

In Latin: aliquid quo nihil maius cogitari potest

What does this mean?:

- God is the greatest possible being

- There is no being greater than God

- God has every perfection (every property that makes something "great")

- You cannot conceive of anything superior to God

The word "conceive" is crucial. Anselm means: anything that your mind can possibly think of or imagine.

The Logical Structure: The Argument

Anselm's argument can be laid out in logical steps:

P1: God is defined as "a being than which nothing greater can be conceived"

P2: Even "the fool" (the atheist) understands this definition—he can think of this concept

P3: Whatever is understood exists in the mind (as an idea)

P4: If something exists only in the mind but not in reality, then something greater can be conceived—namely, that same thing existing in reality

P5: But by definition, nothing greater than God can be conceived

C1: Therefore, God cannot exist only in the mind

C2: Therefore, God must exist in reality (in addition to existing in the mind)

The Key Insight: Existence as a Perfection

The crucial move in Anselm's argument is treating existence as a perfection (a "great-making property"):

- A being that exists is greater than a being that doesn't exist, all else being equal

- Example: A real pizza is better/greater than an imaginary pizza. Existence is part of what makes something greater

- Therefore, if God is the greatest conceivable being, God must have every perfection, including existence

- Without existence, God would lack a perfection and wouldn't be the greatest conceivable being

The Reductio ad Absurdum Structure

Anselm's argument works by reduction to absurdity (reductio ad absurdum):

- Suppose God exists only in the mind (the atheist's position)

- Then we could conceive of something greater: a God that exists in both mind and reality

- But this contradicts the definition of God as "that than which nothing greater can be conceived"

- Therefore, the supposition must be false

- God cannot exist only in the mind

- So God must exist in reality

Proslogion Chapter 3: The Stronger Version

Anselm develops a stronger version of his argument in Chapter 3 of the Proslogion:

- In Chapter 2, Anselm shows that God must exist

- In Chapter 3, Anselm goes further—God must exist necessarily (God cannot not exist)

The Argument:

P1: God is "that than which nothing greater can be conceived"

P2: A being whose non-existence is impossible is greater than a being whose non-existence is possible

P3: If God's non-existence were possible, we could conceive of something greater—a God whose non-existence is impossible

P4: But nothing is greater than God

C: Therefore, God's non-existence is impossible. God is a necessary being—God must exist and cannot not exist

What Makes This Argument Unique

Unlike the cosmological argument (which observes motion, causation, contingency), Anselm's argument is:

- A priori – It doesn't depend on experience or observation of the world

- Purely logical – It depends only on the definition of God and logical reasoning

- Deductive – If the premises are true, the conclusion must be true

- Analytical – It analyzes the concept of God itself

This is why it's called ontological—from "ontology," the study of being or existence. It tries to derive existence from the concept of being itself.

A Key Challenge: Gaunilo's Perfect Island

Almost immediately after Anselm published his argument, a monk named Gaunilo raised an objection:

Gaunilo's Parody:

Suppose we define "the perfect island" as "an island than which no greater island can be conceived." By Anselm's logic, this perfect island must exist, because:

- We understand the concept

- A greater island (one that actually exists) can be conceived

- Therefore, the perfect island must exist in reality

But this is absurd! We can't prove that a perfect island exists just by defining it.

Gaunilo's Conclusion:

If Anselm's logic leads to the absurd conclusion that the perfect island exists, then Anselm's argument itself must be flawed.

Anselm's Reply:

Anselm responds that the argument only works for God, not for islands or other contingent things. Why?:

- Islands are contingent—they might exist or might not; their existence is not necessary

- An island could be destroyed; it's not essentially eternal

- For an island, we could always conceive of a greater island—with more beaches, better weather, no need for maintenance, etc.

- The concept of an island is not in itself a greatest conceivable thing

- But God is defined as the greatest conceivable being—literally nothing can be greater

- So the argument works uniquely for God, not for arbitrary things

Modern philosophers like Alvin Plantinga argue that "that than which nothing greater can be conceived" is a unique description that applies only to God, not to islands.

Kant's Critique: Existence Is Not a Predicate

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) offered the most famous criticism of the ontological argument in his Critique of Pure Reason:

Kant's Objection:

Existence is not a predicate (not a property or quality that can be added to a concept).

What does this mean?:

- When you list the properties of something—like a gold coin—you might say: round, yellow, metallic, valuable

- But "exists" is not one of these properties

- Why? Because "exists" is not part of the concept of the thing; it's whether the thing is instantiated (actually realized) in reality

Kant's Example:

Imagine two job candidates with identical CVs listing identical qualifications. The only difference is that one candidate actually exists (shows up to the interview) while the other is fictitious. You wouldn't say the real candidate is "greater" because he has the additional predicate "exists." Rather, he's real and the other is not. Existence doesn't add a perfection; it's whether the bundle of perfections actually exists in reality.

Application to Anselm:

- If existence is not a predicate, then you can't argue that a perfect being must exist simply because perfection includes existence

- You can define a perfect being in your concept, but that doesn't make it exist in reality

- Defining something as having all perfections doesn't guarantee that the concept is realized

Response from Defenders:

Modern defenders of Anselm (like Charles Hartshorne and Norman Malcolm) have argued that Kant only dealt with contingent existence:

- For contingent things, Kant is right—existence is not a predicate

- But for a necessary being, necessity might be a predicate

- And if a necessary being is possible, then it must exist

- This shifts the debate to whether God's non-existence is truly impossible (logically contradictory)

Modern Developments

The ontological argument has been reformulated by several modern philosophers:

- Kurt Gödel (1906-1978) created a sophisticated modal logic version using symbolic logic

- Charles Hartshorne and Norman Malcolm defended modal versions emphasizing necessity rather than just existence

- Alvin Plantinga developed what some consider the strongest contemporary modal ontological argument, though Plantinga himself is cautious about claiming it "proves" God's existence

These modern versions avoid Kant's objection about existence by focusing on necessary existence rather than existence as a simple predicate.

Scholarly Perspectives

"Hence, even the fool is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater."

"Being is obviously not a real predicate; that is, it is not a concept of something that could be added to the concept of a thing. It is merely the positing of a thing, or of certain determinations, as existing in themselves."

Key Takeaways

- ✓Anselm's argument is a priori—purely from reason, not observation of the world

- ✓It defines God as 'that than which nothing greater can be conceived'

- ✓The key move: existence is a perfection (makes something greater)

- ✓The logical structure: reductio ad absurdum—suppose God doesn't exist in reality, then something greater could be conceived

- ✓This contradicts the definition of God, so God must exist

- ✓Proslogion Chapter 3 makes it stronger: God must exist necessarily (cannot not exist)

- ✓Gaunilo's perfect island objection: Why doesn't the same logic prove islands, donuts, unicorns exist?

- ✓Anselm's response: The argument only works for God, not contingent things like islands

- ✓Kant's critique is most famous: Existence is not a predicate (property) that can be added to a concept

- ✓Kant argues: Defining something doesn't make it real; concept ≠ actual existence

- ✓Modern defenders use modal logic to focus on necessary existence instead of existence as a predicate

- ✓The debate continues: Whether the ontological argument works remains controversial among philosophers