Kant's Criticisms

Summary

Kant developed the most influential criticism of the ontological argument in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781). He makes two main points: (1) Existence is not a predicate (property) — adding "exists" to a concept doesn't change the concept, just like 100 real coins are identical to 100 imaginary coins; they're still just 100 coins. So claiming that God must exist because existence is a "perfection" is confused. (2) Denying God's existence is not self-contradictory — we can deny God exists without contradicting the definition of God, just like we can deny a triangle exists without denying that triangles have three sides. Therefore, the ontological argument fails because it assumes something false: that existence is a predicate that can be deduced from a concept.

Detailed Explanation

Who Was Immanuel Kant?

- Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was a German Enlightenment philosopher and one of the most important figures in Western philosophy

- He worked in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), and rarely left his hometown

- His major work is the Critique of Pure Reason (first edition 1781, revised 1787), which fundamentally transformed philosophy

- Kant coined the term "ontological argument" — before him, no one called Anselm's and Descartes' arguments "ontological"

- Kant used this term because these arguments try to derive existence (being/ontology) from reason alone, without any experience

Kant's Two Main Criticisms

Kant offers two distinct criticisms of the ontological argument:

- Existence is not a predicate (the most famous)

- Denying God's existence is not self-contradictory (a distinct but related point)

Criticism 1: Existence Is Not a Predicate

What Is a Predicate?

A predicate is a property or quality that describes something. Examples of predicates:

- In "The cat is black," "black" is a predicate—it describes a property of the cat

- In "The car is fast," "fast" is a predicate

- In "God is omnipotent," "omnipotent" is a predicate—it ascribes a property to God

Predicates add information or qualities to the concept of a thing.

Kant's Core Claim

"Being is evidently not a real predicate, that is, a conception of something which is added to the conception of some other thing."

What does this mean? When you add a predicate to a concept, you add a new quality or property. But when you add "exists," you don't add anything to the concept itself. You merely posit (assert) that the concept is instantiated in reality.

Example:

- Concept A: "a being with omnipotence, omniscience, and moral perfection"

- If you add "exists": "a being with omnipotence, omniscience, moral perfection, AND existence"

- But has the concept changed? No—it's still a being with those three properties

- Existence doesn't add a fourth property to the concept

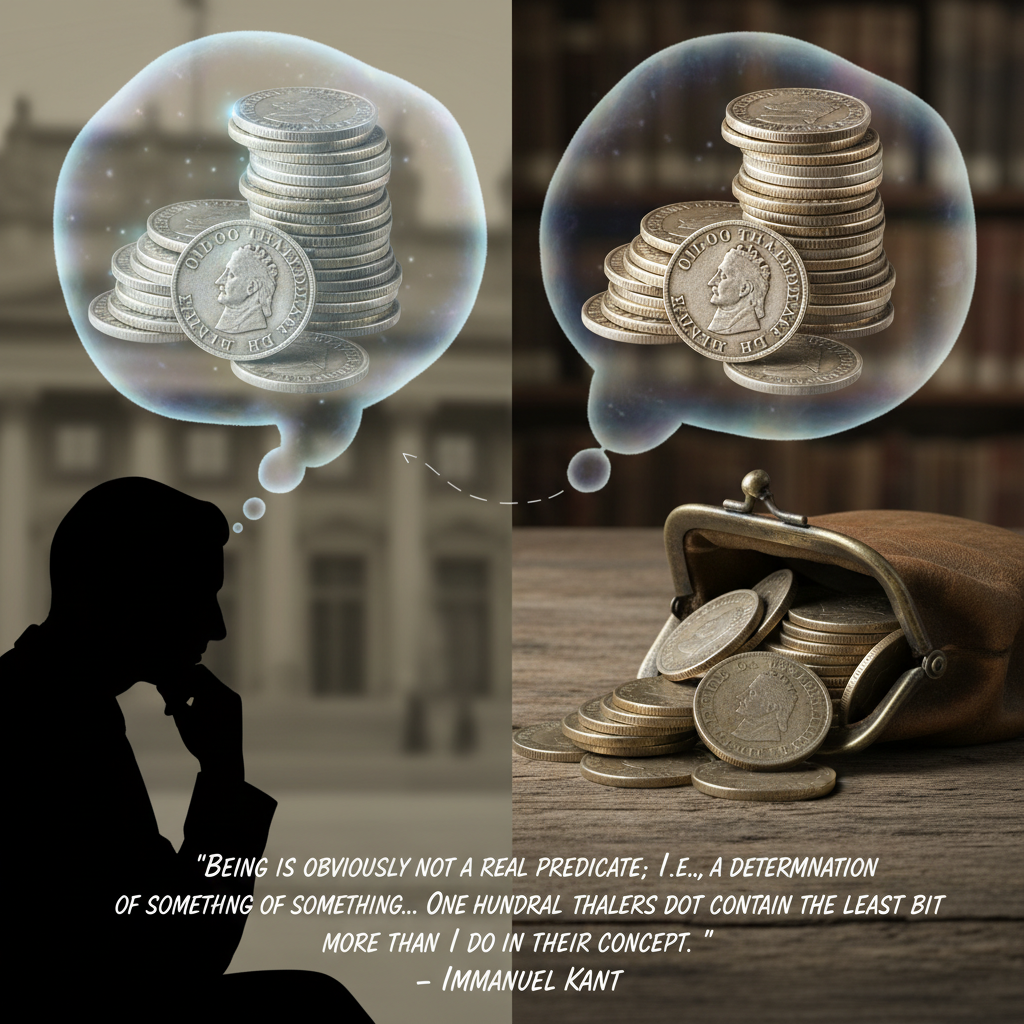

The Hundred Thalers Analogy

Kant's most famous illustration is the "hundred thalers" analogy (thalers were German coins):

Kant's Thought Experiment:

- Imagine 100 thalers in your mind (a concept)

- Now imagine 100 thalers in your pocket (real money)

- What's the difference? Do the real thalers have something the conceptual thalers lack?

Kant's Conclusion:

- The real thalers are not "101 thalers" or "150 thalers" or in any way a greater number than the conceptual thalers

- They're still just 100 thalers—identical to the concept

- Existence hasn't added anything to the concept of "100 thalers." It's still 100 coins—no more, no less

Application to God: If you conceive of God as having all perfections, and if existence is a perfection, then you must add "existence" to the concept, making God real. But Kant's response: No, adding "exists" doesn't change what God is. It doesn't add a new perfection or property. It merely asserts that the concept of God is instantiated in reality. But asserting that a concept exists doesn't logically follow from the concept's content.

The Analytic vs. Synthetic Distinction

Kant also appeals to the analytic/synthetic distinction:

- Analytic proposition: A statement whose truth can be determined just by understanding the concepts involved (e.g., "All bachelors are unmarried"). The predicate is contained in the subject.

- Synthetic proposition: A statement that adds new information; its truth requires going beyond mere concepts (e.g., "It is raining").

Kant's Argument: All existential statements are synthetic, not analytic. Why? Because existence is not part of the concept itself; you must go beyond the concept to check if it's instantiated in reality. Therefore, "God exists" is synthetic, not analytic. And since Anselm's argument tries to derive existence analytically (just from the concept), it fails.

Criticism 2: Denying God's Existence Is Not Self-Contradictory

The Structure of Analytic Denials

Anselm's argument depends on showing that denying God's existence is self-contradictory. If you can coherently deny God's existence, then God's existence doesn't follow logically from the concept.

Kant's Distinction: It's true that some denials are self-contradictory. You cannot coherently deny that "a triangle has three angles" while affirming that "a triangle exists." If a triangle exists, it necessarily has three angles—denying this is contradictory. But you CAN coherently deny that triangles exist at all.

Kant's Famous Quote:

"It would be self-contradictory to posit a triangle and yet reject its three angles, but there is no contradiction in rejecting the triangle together with its three angles."

Application to God

- What is contradictory: To affirm God exists AND deny that God is omnipotent, omniscient, etc.

- What is NOT contradictory: To deny God exists altogether

Why? Because the connection between the concept "God" and the assertion "exists" is not an internal connection (like three angles to a triangle). Rather, it's an external assertion that the concept is instantiated. You can coherently say: "The concept 'God' is internally consistent, but nothing actually exemplifies this concept."

Modern Defenses Against Kant's Criticisms

Response 1: Distinguish Contingent from Necessary Existence

Many modern defenders argue Kant is only correct about contingent things:

- For contingent beings (like thalers, coins, tables): Existence doesn't add a perfection; Kant is correct

- For necessary beings (like God): Necessary existence might be different; it might be a predicate in a way contingent existence is not

Philosopher Charles Hartshorne argues that "necessary existence is a superior manner of existence" to contingent existence. Anselm's point was never that ordinary existence is a perfection, but that necessary, indestructible existence is a perfection. Kant's hundred thalers analogy compares contingent existence to contingent existence, which misses Anselm's point about God being a necessary being.

Response 2: The Possibility Entails Actuality Argument

Modern modal logicians like Alvin Plantinga argue: If God (as the greatest conceivable being) is even possibly possible, then God must exist. Why? Because if God's non-existence were possible, then God would not be the greatest conceivable being (since a being that necessarily exists would be greater). This avoids Kant's objection by shifting to modal logic rather than treating existence as a predicate.

Response 3: Hegel's Critique of Kant

Friedrich Hegel responded directly to Kant's hundred thalers analogy, arguing that Kant made an error by comparing finite, contingent coins with infinite, necessary being (God). When God is regarded as the whole of being (infinite and necessary), not just "one being among many," the ontological argument makes more sense.

Assessment: Is Kant's Criticism Valid?

Philosophers agree Kant identified a real problem, but debate how serious it is:

Those who favor Kant's criticism:

- Existence clearly doesn't add a predicate

- The hundred thalers analogy is intuitively compelling

- The argument confuses conceptual necessity with actual existence

- Anselm wrongly assumes denying God's existence is self-contradictory

Those who favor defenders of Anselm:

- Kant only addressed contingent existence, not necessary existence

- For necessary beings, existence might work differently than for contingent things

- Kant's analogy with finite coins misses the point about infinite being

- Modern modal versions avoid Kant's objection

Most philosophers think Kant successfully refutes naive versions of the ontological argument. But whether he refutes sophisticated modern versions (especially modal logic versions) remains genuinely debated. Kant himself believed God exists, but not as a conclusion from pure reason. Instead, Kant argued God is a "postulate of practical reason" — something we must assume to make sense of morality.

Scholarly Perspectives

"A hundred real thalers do not contain the least coin more than a hundred possible thalers. For as the latter conception has reference to the subject only as a mode of conceiving it, the former has reference to the subject as it exists. But the object, as it really exists, is not analytically contained in my conception, which is merely a possibility. By whatever, and by however many, predicates—even to the complete determination of a thing—I may cogitate a thing, I do not in the least augment the object of my conception by the addition of the statement: This thing is."

"It would be self-contradictory to posit a triangle and yet reject its three angles, but there is no contradiction in rejecting the triangle together with its three angles."

Key Takeaways

- ✓Kant developed the most influential criticism of the ontological argument

- ✓He coined the term 'ontological argument' to describe such arguments

- ✓Criticism 1: Existence is not a predicate — it doesn't add anything to a concept

- ✓The hundred thalers example: 100 real coins are identical to 100 imaginary coins; existence adds nothing

- ✓Adding 'exists' merely posits that the concept is instantiated in reality, not that the concept itself has changed

- ✓All existential statements are synthetic, not analytic — they require going beyond the concept

- ✓Criticism 2: Denying God's existence is NOT self-contradictory

- ✓You can deny a triangle's existence while affirming all its properties — no contradiction

- ✓So Anselm's reductio ad absurdum fails — denying God exists isn't logically impossible

- ✓Modern defenders argue Kant only addressed contingent things, not necessary beings

- ✓For necessary beings, existence might work differently—necessary existence might be a predicate

- ✓Most philosophers think Kant refuted naive versions but debate whether sophisticated versions succeed

- ✓Kant himself believed God exists as a practical postulate, not through pure reason