Paley's Teleological Argument

Summary

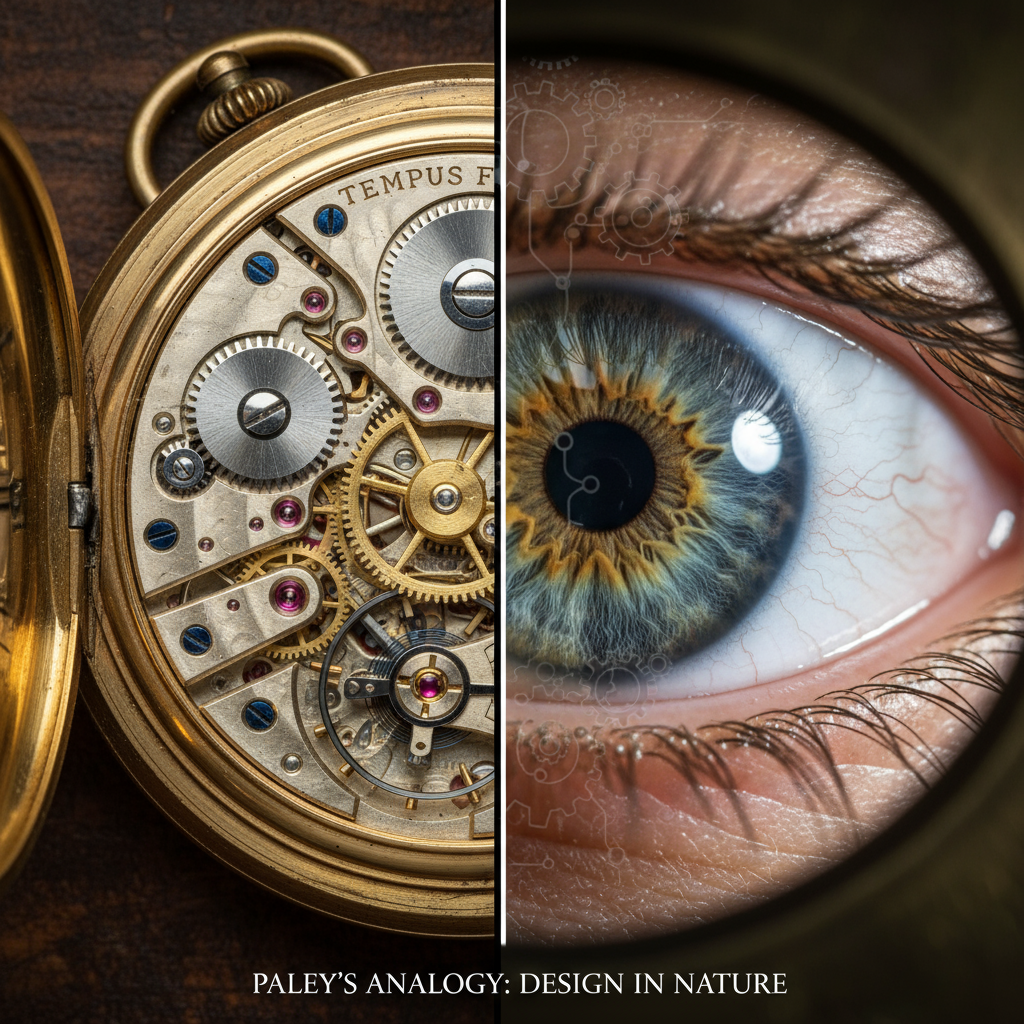

Paley argues that if you found a watch on the ground, you would immediately know someone designed it—its complexity and purpose prove it has a watchmaker. The universe is vastly more complex than a watch, with intricate designs like the human eye, planetary orbits, and adapted animal parts. If a watch needs a maker, then the infinitely more complex universe must need a designer too. That designer is God.

Paley calls this "Design qua Purpose" (design shown through the complexity and purposiveness of things) and "Design qua Regularity" (design shown through the lawful, orderly operation of nature).

Detailed Explanation

Who Was William Paley?

William Paley (1743-1805) was an English theologian and philosopher. His most famous work is Natural Theology; or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, Collected from the Appearances of Nature, published in 1802.

In this book, Paley presents what is arguably the clearest and most persuasive version of the teleological argument (argument from design) for God's existence. Unlike more abstract philosophical arguments, Paley's argument uses intuitive, everyday examples that make it accessible and powerful.

The Watch Analogy: The Core of Paley's Argument

Paley's central argument begins with a famous thought experiment—the watch analogy:

The Stone

Imagine: You are walking across an open field (a heath) and you find a stone. Someone asks you how the stone got there. You might answer that you don't know—perhaps it's always been there. This answer seems reasonable. After all, stones are natural objects, and there's nothing obviously strange about finding a stone in nature.

The Watch

But now imagine: Instead of a stone, you find a watch lying on the ground. Someone asks how the watch came to be there. You would not give the same answer. You would not say, "Perhaps the watch has always been here" or "Perhaps it occurred by chance".

Why? Because the watch displays obvious marks of design and purpose:

- Its parts are complex and numerous

- The parts fit together precisely

- They work together toward a specific end: to tell the time

- This arrangement could not happen by accident

- There must have been a watchmaker—an intelligent designer who created the watch with the purpose of telling time

The key insight: When we observe complexity and purposeful arrangement of parts working together to achieve an end, we infer the existence of an intelligent designer—we don't appeal to chance or say it always existed.

Applying the Analogy to Nature

Paley's brilliant move is to apply this same reasoning to the natural world: Just as the watch has complexity and purpose, so do natural things. In fact, natural objects display vastly greater complexity than any watch.

The Human Eye

Paley argues that the human eye is far more intricate than any human-made device. The eye has multiple components—the cornea, lens, retina, optic nerve—all precisely arranged to work together for a specific purpose: vision. This coordinated complexity cannot have arisen by chance.

By the same reasoning that proves a watch had a maker, the eye must have had a designer. Paley states: "There is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision, as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it".

Adapted Animal Parts

Paley catalogs numerous examples of animal parts exquisitely adapted to their function:

- Joints that function exactly like human-designed hinges or ball-and-socket joints

- Wings of birds perfectly designed for flight

- Hearts perfectly designed to pump blood

- Teeth shaped for eating particular foods

- Hooves and feet adapted for different terrains

Each adaptation shows complexity arranged for a purpose.

The Regularity of the Cosmos

Paley also points to the orderly, mathematical regularity of the universe as evidence of design:

- Planets orbit in regular patterns following Newton's laws

- Gravity operates consistently everywhere

- The laws of physics are uniform and reliable

This regularity (what Paley calls "Design qua Regularity") shows that nature is governed by intelligently designed principles.

Two Types of Design Evidence: Purpose and Regularity

Paley distinguishes two ways that design manifests in nature:

1. Design qua Purpose ("Design by Purpose")

This is design revealed through the complexity and purposiveness of things. Examples include the eye being designed for seeing, the heart for pumping blood, bird wings for flying. Individual structures are intricately designed to achieve specific purposes.

2. Design qua Regularity ("Design by Regularity")

This is design revealed through the lawful, orderly operation of nature. Examples include the regular motion of planets, the consistent operation of gravity, the mathematical principles underlying nature. The fact that nature operates according to reliable, repeatable laws shows intelligent design.

Together, purpose and regularity provide cumulative evidence for God's design.

The Logical Structure of Paley's Argument

Although Paley presents his argument as an analogy, scholars argue it can be interpreted as a deductive argument:

Premise 1: Anything that has several parts arranged in a coordinated way to serve a specific purpose exhibits design.

Premise 2: The universe (and natural objects within it) has multiple parts arranged in a coordinated way to serve specific purposes.

Conclusion: Therefore, the universe exhibits design and must have an intelligent designer.

This deductive reading avoids some criticisms of analogical arguments, because it doesn't depend on the analogy being perfect—it depends on recognizing a property (functional complexity) that reliably indicates design.

Design Does Not Collapse at Imperfections

An important part of Paley's argument is that the inference to design remains valid even when the design is imperfect: Just as a watch can go wrong, run irregularly, and still be clearly a designed object (not something that arose by chance), so nature can have defects, irregularities, and problems while still being designedly created.

A slightly defective watch is still obviously a watch made by a watchmaker. Similarly, a universe with pain, disease, and suffering can still be the design of an intelligent creator.

The argument for design is cumulative and independent for each example:

As Paley argues: "The proof is not a conclusion which lies at the end of a chain of reasoning, of which chain each instance of contrivance is only a link, and of which, if one link fail, the whole falls; but it is an argument separately supplied by every separate example.... The eye proves it without the ear; the ear without the eye".

In other words, each instance of apparent design (the eye, the ear, the heart, the planets) is independent evidence for design. The argument doesn't collapse if we find some parts of nature that seem disorderly.

Paley's Attributes of God

From his design argument, Paley concludes that God must have certain attributes:

- Intelligence: To have designed such complexity

- Power: To create such a vast, complex universe

- Benevolence/Goodness: Because much of the design in nature produces pleasure and benefit for creatures

- Unity: There is one coherent design throughout nature, suggesting one designer

Hume's Criticisms and Paley's Responses

Paley was aware of criticisms by David Hume (from his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion):

Hume's objection: Watches are artificial, human-made objects. The universe is natural. These are too dissimilar to argue by analogy that the universe has a designer just because a watch does.

Paley's response: The argument doesn't rest on analogy in the way Hume attacks. Paley isn't saying "watches are like the universe, so probably the universe is designed".

Rather, Paley is identifying a reliable indicator of intelligent design: functional complexity (multiple parts organized to serve a purpose). Both watches and natural objects (eyes, hearts, etc.) exhibit this property. Therefore, both warrant an inference to design, not because they're similar in other ways, but because they both exhibit this key property that indicates intelligent design.

Darwin and Evolution: The Great Challenge

Paley's argument was profoundly challenged by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection:

- Evolution explains how complexity and apparent design can arise in nature without an intelligent designer

- Random mutations combined with natural selection produce complex, well-adapted organisms

- The appearance of design (eyes, wings, hearts) emerges through this blind, undirected process over millions of years

- Therefore, we don't need to infer an intelligent designer to explain apparent design in living things

However, Paley's argument is not completely undermined by evolution:

- Modern teleological arguments often point to order beyond what can be found within nature—such as the laws of nature themselves (gravity, electromagnetism, quantum mechanics)

- These laws are so finely tuned to allow for the possibility of life that they seem designed

- This type of order in the laws of nature (called "temporal order") cannot be explained by evolution, only by appeal to an intelligent designer or to brute chance

The Cumulative Case

An important strength of Paley's argument is that it is cumulative:

- It's not a chain of reasoning where one broken link brings down the whole argument

- Rather, each example of apparent design (the eye, the ear, the heart, planetary orbits, adapted animal parts) provides independent evidence

- Even if some examples fail, others remain

This makes the argument resilient—it doesn't depend on any single example being perfectly convincing.

Scholarly Perspectives

"In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone, and were asked how the stone came to be there; I might possibly answer, that, for anything I knew to the contrary, it had lain there forever... But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place; I should hardly think of the answer I had before given... There must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers, who formed [the watch] for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use."

"Every indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater or more, and that in a degree which exceeds all computation."

Key Takeaways

- ✓Paley's watch analogy is the core of his argument—finding a watch proves a watchmaker; nature proves a designer

- ✓Functional complexity is the key indicator of design—multiple parts organized to serve a specific purpose

- ✓Two types of design evidence: Design qua Purpose (purposeful complexity) and Design qua Regularity (lawful order)

- ✓Natural objects like the eye show vastly greater design than any watch—therefore demand an intelligent designer

- ✓Paley's argument is cumulative—each example of design is independent evidence, not dependent on others

- ✓Defects don't negate design—a faulty watch is still a designed object, as is an imperfect universe

- ✓Paley concludes God must be intelligent, powerful, benevolent, and unified

- ✓Evolution is a major challenge—it explains biological design without needing a designer

- ✓But evolution doesn't explain everything—the fine-tuning of physical laws still seems to require design

- ✓Paley's argument can be read as deductive, not just analogical—this avoids some philosophical criticisms

- ✓The watchmaker analogy remains one of the most intuitive and powerful arguments for God's existence

- ✓Even modern physics has revived interest in the design argument through the fine-tuning problem