Omnibenevolence

Summary

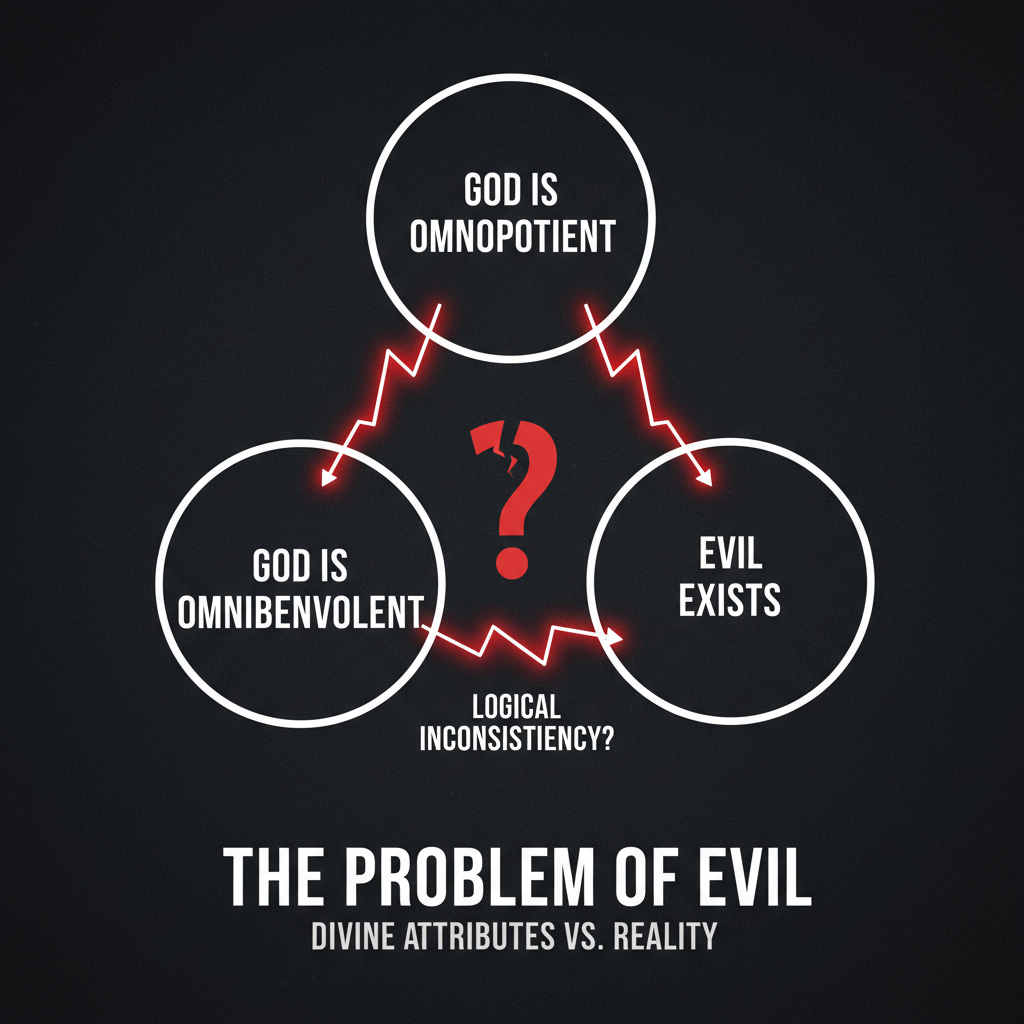

Omnibenevolence means "all-good" or "perfectly loving"—God is maximally good in both a metaphysical sense (God is supremely perfect) and a moral sense (God's will always aligns with what is morally good). God's omnibenevolence manifests in His agape love—unconditional, selfless love not caused by anything we do. The major philosophical problem: omnibenevolence seems incompatible with evil. If God is perfectly good and all-powerful, why does evil exist? This creates Mackie's inconsistent triad: (1) God is omnipotent, (2) God is omnibenevolent, (3) Evil exists—only two can be true. Omnibenevolence also relates to Divine Command Theory: is something good because God commands it (making morality arbitrary), or does God command it because it's good (making God subject to external moral law)? Modified Divine Command Theory solves this: God's commands flow from His unchanging omnibenevolent nature.

Detailed Explanation

What Is Omnibenevolence?

Omnibenevolence comes from Latin: omni (all) + bene (good) + volens (willing).

Basic Definition:

- God is perfectly good—maximally good in every way possible

- God is all-loving—His nature is intrinsically loving

Two Dimensions of Omnibenevolence

1. Metaphysical Goodness (Perfection):

- God is supremely perfect—"that than which nothing greater can be conceived" (Anselm)

- God is "every perfection" (First Vatican Council)

- Goodness = perfection; to say God is omnibenevolent is to say God is metaphysically perfect

Aquinas' View:

"God loves all existing things. For all existing things, in so far as they exist, are good, since the existence of a thing is itself a good."

God's love extends to all of creation because existence itself is good.

2. Moral Goodness (Perfect Will):

- God's will (intention) always aligns with what is morally good

- God never does anything bad or evil

- God always acts in accordance with perfect moral goodness

Characteristics of God's Love (Agape)

Agape Love: The Greek New Testament word for God's love is agape—unconditional, selfless love.

Key Features:

Uncaused

- God's love doesn't have a cause

- He doesn't love us because of anything specific we do

- It's just part of His nature to love

Intrinsic

- God is intrinsically loving—it's part of His essence

- It's not caused or influenced by humanity

- Love is who God is, not just what God does

Unconditional

- God loves regardless of merit or worthiness

- The resurrection of Christ is seen as God's ultimate expression of agape love

The Problem of Evil and Omnibenevolence

Mackie's Inconsistent Triad

The Central Challenge: Omnibenevolence creates the most serious philosophical problem for theism—the problem of evil.

J.L. Mackie's Inconsistent Triad:

Three propositions that cannot all be true simultaneously:

- 1. God is omnipotent (all-powerful)

- 2. God is omnibenevolent (all-good)

- 3. Evil exists

The Logical Argument:

- P1: An omnipotent God has the power to eliminate evil

- P2: An omnibenevolent God has the motivation to eliminate evil

- Additional Premise: A good being always eliminates evil as far as it can

- P3: Nothing can exist if there is a being with both the power and motivation to eliminate it

- C: Therefore, omnipotence, omnibenevolence, and evil form an inconsistent triad—they cannot all be true

The Dilemma for Theists: Since evil clearly exists, either:

- God is not omnipotent (lacks power to stop evil), OR

- God is not omnibenevolent (doesn't want to stop evil)

Both conclusions contradict classical theism.

Why This Challenges Omnibenevolence Specifically

Hume's Point:

If God were omnibenevolent, He would want to eliminate all suffering. If He doesn't eliminate suffering despite having the power, then either He is not actually omnibenevolent, OR He is not actually omnipotent.

Questions Raised:

- How can a loving God allow people to do evil things?

- Why do good people need to suffer?

- If God is omnipotent and omnibenevolent, why does He allow evil and suffering to exist?

John Stuart Mill's Criticism

Mill openly criticized the idea of an omnibenevolent God, particularly attacking the design argument.

Mill's Argument: God cannot be loving if He created a world where:

- Animals must kill each other to survive

- Natural disasters destroy innocent lives

- Suffering is widespread and often pointless

The design of nature suggests either God is not perfectly good, OR God is not the designer.

Responses to the Omnibenevolence-Evil Problem

Response 1: Aquinas' "Master Plan" Defense

Aquinas' Argument:

- We cannot judge the seemingly unjust world around us because we do not know God's "master plan"

- Events may seem to cause suffering, but there may be a greater outcome we cannot see

- God's ways are higher than our ways; His purposes transcend our understanding

Aquinas' Additional Point:

- God understands our suffering and can empathize with us

- Through the Incarnation (Jesus), God entered time and experienced suffering Himself

- This demonstrates God's omnibenevolence even in allowing suffering

Criticism:

- This response doesn't explain why God allows suffering—it just says we can't understand

- It asks us to trust God despite the evidence, which seems like avoiding the problem rather than solving it

Response 2: Kant's Moral Argument (Afterlife Solution)

Kant's Argument: God's omnibenevolence is redeemed in heaven. While evil exists in this life, ultimate justice and goodness are achieved in the afterlife.

The Logic:

- In this world, the virtuous often suffer and the wicked often prosper

- A perfectly good God must ensure ultimate justice

- Therefore, there must be an afterlife where wrongs are righted

Criticism:

- Does future compensation truly justify present suffering?

- Can heaven "make up for" the torture of an innocent child?

Response 3: Theodicies (Augustine & Hick)

These have been covered extensively in previous lessons:

Augustine's Theodicy:

- Evil is privatio boni (absence of good)

- God didn't create evil; humans did through misuse of free will

- Natural evil results from living in a fallen world

Hick's Theodicy:

- World is a "vale of soul-making"

- Suffering develops moral virtue and spiritual maturity

- Universal salvation justifies temporary suffering

Criticism:

- While theodicies offer explanations, they don't fully eliminate the logical contradiction

- The debate continues over whether any theodicy successfully reconciles omnipotence, omnibenevolence, and evil

Omnibenevolence and Divine Command Theory

What Is Divine Command Theory?

Divine Command Theory (DCT): The view that morality is determined by God's commands. An action is morally right if and only if God commands it. An action is morally wrong if and only if God forbids it.

The Motivation:

- DCT attempts to ground morality in a theistic framework

- It gives moral obligations an objective, mind-independent foundation

- If God exists and commands moral behavior, then morality is not merely subjective human opinion

The Euthyphro Dilemma

The Ancient Problem: Plato's dialogue Euthyphro poses a famous dilemma for DCT.

The Question: "Is something good because God commands it, OR does God command it because it is good?"

The First Horn: Good Because God Commands It

If things are morally right because God commands them:

Implication 1 (Arbitrariness):

- Morality becomes arbitrary

- If God commanded cruelty, torture, or genocide, those would be morally good

- There's no reason why God commands what He does—He just does

Implication 2 (Meaningless to Call God "Good"):

- If "good" just means "what God commands," then "God is good" is trivial

- It's like saying "God does what God does"—empty tautology

- We lose the independent standard to praise God's goodness

The Second Horn: God Commands Because It's Good

If God commands things because they are already morally good:

Implication 1 (External Moral Standard):

- There's a moral standard external to and independent of God

- God is subject to this external standard

- God is no longer sovereign—something else (morality) is greater than God

Implication 2 (God Not Omnipotent):

- If goodness is not a matter of God's command, God cannot change what is good/bad

- There's something God lacks the power to do

- This contradicts omnipotence

Implication 3 (God Not the Foundation of Morality):

- God becomes a mere "recognizer" of right and wrong, not the "author"

- Morality exists independently; God just informs us about it

- This undermines the theistic grounding DCT was trying to achieve

The Problem for Omnibenevolence: Either horn undermines God's omnibenevolence. First horn: God could command evil acts, making Him not truly good. Second horn: God's goodness is derivative, not intrinsic; He's subject to external standards.

Modified Divine Command Theory (Robert Adams)

The Solution: Robert Adams developed Modified Divine Command Theory to escape the Euthyphro dilemma.

Adams' Key Move:

Morality is based not on God's arbitrary commands nor on an external standard, but on God's unchanging omnibenevolent nature.

The Argument:

- P1: God's nature is necessarily and unchangingly omnibenevolent

- P2: God's commands flow from His omnibenevolent nature

- P3: Therefore, God's commands are not arbitrary—they necessarily reflect perfect goodness

- C: God is both the source and the standard of morality

How This Solves the Dilemma:

Solves the Arbitrariness Problem (First Horn):

- God's choices are not arbitrary

- God won't and can't change His mind about what is good because His commands flow from His unchanging omnibenevolent nature

- God commanding cruelty is impossible—it would violate His nature

Solves the External Standard Problem (Second Horn):

- The moral standard is not external to God

- The standard IS God's nature—intrinsic to God Himself

- God is sovereign because morality is grounded in His essence

Implication for Omnibenevolence: God is omnibenevolent because His nature is the standard and source of moral goodness. This defends the claim that God is omnibenevolent against the Euthyphro dilemma.

The Relationship Between Omnibenevolence and Other Attributes

Omnibenevolence and Omnipotence

Potential Conflict: Some argue omnipotence and omnibenevolence are incompatible.

The Argument:

- P1: An omnipotent being can do anything logically possible, including evil acts

- P2: Omnibenevolence means "all good"—unlimited or infinite benevolence

- P3: An omnibenevolent being cannot do evil acts (logically incompatible with being all-good)

- C: Therefore, an omnibenevolent God cannot be omnipotent, because He's unable to do evil

Response:

- Being unable to do evil is not a limitation on omnipotence—it's a consequence of God's perfect goodness

- Just as God cannot create square circles (logical impossibility), God cannot be evil (contradicts His nature)

- Omnipotence means power to do anything consistent with God's nature

Omnibenevolence and Omniscience (Boethius' Problem)

The Problem: If God is omniscient and knows the future, and if God is omnibenevolent and will judge us for our sins, then God cannot be just if we lack free will.

Why This Matters for Omnibenevolence:

- A truly omnibenevolent God must be just in His judgments

- But if we lack free will (because God's foreknowledge determines the future), then God is unjust in punishing us

- Therefore, either God is not truly omnibenevolent, or He doesn't have foreknowledge

Boethius' Solution:

- God is eternal (outside time), not everlasting (within time)

- God sees all time simultaneously in His "eternal present"

- God doesn't have "foreknowledge" but rather sees our free choices as they happen (in the eternal present)

- Therefore, God can judge us fairly for actions we freely choose

- This preserves both omniscience and omnibenevolence

Strengths of the Concept of Omnibenevolence

- Grounds Morality in God: Provides an objective foundation for ethics. Morality is not arbitrary human invention but reflects divine perfection.

- Motivates Religious Devotion: God's perfect love inspires worship and trust. Believers can have confidence in God's goodness even when suffering.

- Makes Sense of Religious Experience: God's agape love explains religious experiences of being loved unconditionally. The Incarnation and Crucifixion express God's omnibenevolent nature.

- Compatible with Justice: A perfectly good God ensures ultimate justice. Rewards the virtuous and punishes the wicked (consistent with moral goodness).

Criticisms and Problems

- The Problem of Evil (Insurmountable?): The existence of horrendous evils seems incompatible with omnibenevolence. No theodicy fully eliminates the inconsistent triad.

- Divine Hiddenness: If God is omnibenevolent, why doesn't He make His existence obvious to everyone? Many sincere seekers never find God—seems inconsistent with perfect love.

- Hell: If God is omnibenevolent, how can He condemn people to eternal torment? Eternal punishment for finite sins seems incompatible with infinite love.

- Natural Evil: Why would a loving God design a world with earthquakes, diseases, and predation? Mill's critique: nature seems cruel, not benevolent.

Scholarly Perspectives

"God loves all existing things. For all existing things, in so far as they exist, are good, since the existence of a thing is itself a good; and likewise, whatever perfection it possesses. Now it has been shown above that God's will is the cause of all things."

"Killing is wrong because it is contrary to the commands of a loving God. The goodness of God's commands does not depend on God's arbitrary choice, nor on some intrinsic standard of goodness external to God, but on God's perfectly loving nature which is intrinsic to God."

Key Takeaways

- ✓Omnibenevolence means perfectly good—metaphysically (perfect) and morally (will aligned with good)

- ✓God's agape love is unconditional, intrinsic, uncaused—part of His nature

- ✓Major challenge: inconsistent triad (omnipotence + omnibenevolence + evil)

- ✓Mackie: only two of three can be true; evil exists, so God lacks omnipotence or omnibenevolence

- ✓Mill's critique: nature's cruelty (predation, disasters) incompatible with loving God

- ✓Aquinas' response: we don't know God's master plan; trust despite not understanding

- ✓Kant's response: omnibenevolence redeemed in afterlife through ultimate justice

- ✓Euthyphro dilemma: good because God commands it OR God commands because it's good?

- ✓First horn: morality arbitrary; God could command cruelty

- ✓Second horn: external moral standard; God not sovereign

- ✓Adams' Modified DCT: morality grounded in God's unchanging omnibenevolent nature

- ✓Boethius: omnibenevolence requires just judgment; solved by God being eternal (outside time)

- ✓Problem of evil remains most serious challenge to omnibenevolence