The Categorical Imperative: Unconditional Moral Law

Summary

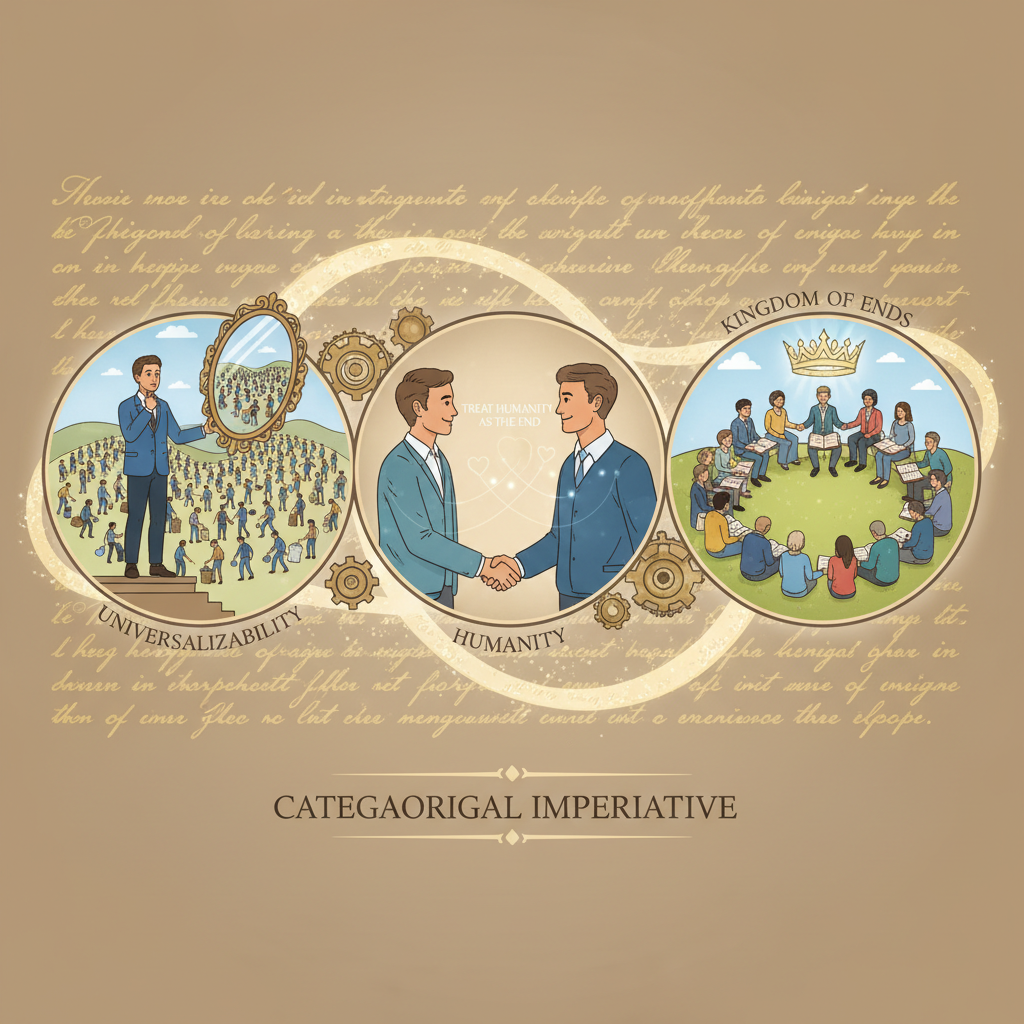

The Categorical Imperative (CI) is Kant's supreme moral rule. Unlike hypothetical imperatives (which are conditional: "If you want X, do Y"), the Categorical Imperative is unconditional: it commands "Do X" simply because it is the right thing to do, regardless of your desires. Kant gave three formulations (ways of stating) this one rule to help us work out our duty: (1) Universalizability—act only on rules that you would be willing to make a universal law for everyone (like "Do not steal"); (2) Humanity—always treat people (including yourself) as valuable ends in themselves, never just as tools (means) to get what you want; (3) Kingdom of Ends—act as if you are a law-maker in a perfect community where everyone treats everyone else with dignity. If an action fails these tests (like lying), it is morally wrong, no matter the consequences.

Detailed Explanation

What Is the Categorical Imperative?

Definition

- It is the absolute, unconditional moral command derived from reason. It tells us our duty. It applies to all rational beings, at all times, regardless of their personal wants or goals.

Contrast with Hypothetical Imperatives

Hypothetical

"If you want to be trusted, tell the truth." (Depends on desire).

Categorical

"Tell the truth." (Depends on reason/duty).

The Three Formulations

Kant believed these were three ways of saying the same basic thing, but they highlight different aspects of morality.

1. The Formula of Universal Law (Universalizability)

The Principle

"Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law."

How to use it (The "Universalizability Test"):

- Identify your maxim: What is the rule behind your action? (e.g., "I will lie to get money").

- Universalize it: Imagine a world where everyone followed this rule as a law of nature.

- Check for contradiction:

- Contradiction in Conception: Is this world logically possible? If everyone lied to get money, promises would mean nothing, and "borrowing" would be impossible. The concept destroys itself.

- Contradiction in Will: Would you rationally want to live in this world? Youcan't rationally will a world where no one helps others, because you might need help yourself one day.

- Result: If it fails, the action is wrong.

Example: The Lying Promise

- You need money, so you promise to pay it back knowing you can't.

- Maxim: "Make a false promise to get what I want."

- Universalized: Everyone makes false promises.

- Result: Trust collapses. Promises cease to exist. This is a contradiction in conception. Therefore, lying is strictly forbidden.

2. The Formula of Humanity (End in Itself)

The Principle

"Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, always as an end and never as a means only."

What it means:

- End in itself: Humans have intrinsic value/dignity because they are rational agents. We must respect their rights and autonomy.

- Means only: You can use people (e.g., a taxi driver is a means to get somewhere), but you cannot use them merely as a means. You must still respect them as a person (pay them, be polite). Slavery, deception, and coercion treat people merely as objects/tools.

Applying it

Lying to someone treats them as a tool to get money. It bypasses their rationality because they cannot consent to the true nature of the transaction.

3. The Formula of the Kingdom of Ends

The Principle

"Act as if you were through your maxims a law-making member of a kingdom of ends."

What it means:

- Imagine a perfect community (Kingdom) where everyone treats everyone else as an end (with dignity). You should act now as if you live in that world, creating laws that would be accepted by the whole community.

- It combines the first two: universal laws (Formula 1) that respect everyone (Formula 2).

Quick Reference: The Three Formulations

| Formulation | Name | Key Question to Ask | Key Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | Universalizability | "What if everyone did this?" | Logic, Consistency, No exceptions for self |

| Second | Humanity (Ends) | "Am I using this person?" | Dignity, Rights, Respect, Autonomy |

| Third | Kingdom of Ends | "Would this rule work in a perfect society?" | Community, Legislation, Harmony |

Strengths of the Categorical Imperative

Strength 1: Clear, Rational, Universal Rules

The Categorical Imperative provides clear moral rules that apply to everyone, everywhere, always. It is based on reason, not emotion or culture, making it objective.

Strength 2: Protects Human Rights and Dignity (Formula 2)

The Formula of Humanity (treating people as ends, not merely as means) powerfully captures our intuitions about human rights. It forbids slavery, exploitation, deception, and coercion.

Strength 3: Fair—No Special Exceptions

Universalizability prevents you from making exceptions for yourself. If everyone can't do it, neither can you. This ensures fairness.

Strength 4: Does Not Depend on Consequences

Unlike utilitarianism, the Categorical Imperative does not require you to predict or calculate consequences, which can be uncertain or unknowable.

Criticisms of the Categorical Imperative

Criticism 1: Too Inflexible—No Room for Context

The Objection: Kant's rules are absolute. But what if breaking a rule would save a life?

Example: The Murderer at the Door

A murderer asks you where your friend is hiding. Kant says you must tell the truth, even if it gets your friend killed. Many find this counterintuitive—surely lying to save a life is morally right?

Criticism 2: Ignores Consequences Completely

The Objection: Surely consequences matter. If an action causes terrible suffering or harm, isn't that morally relevant? Kant focuses only on intentions and duty, but utilitarians argue that outcomes should count.

Criticism 3: Clashes of Duties

The Objection: What if two duties conflict?

Example

You promised to meet a friend, but on the way you see a car accident and someone needs help. Both keeping promises and helping others are duties. Which should you follow? Kant gives no way to resolve conflicts.

Criticism 4: Maxims Can Be Formulated Differently

The Objection: The test depends on how you phrase your maxim. You could make almost anything permissible by phrasing it carefully.

Example

Instead of "I will lie", you could say "I will lie only when a murderer asks me where my friend is hiding". This specific maxim could be universalized without contradiction.

So the test doesn't give clear answers—it depends on how you describe your action.

Criticism 5: Treating People As Ends Is Vague

The Objection: What exactly does it mean to treat someone as an end? Where is the line between using someone as a means and respecting them as an end? The Formula of Humanity is inspiring but unclear in practice.

Scholarly Perspectives

"Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law."

This is the classic statement of the First Formulation (Universalizability). It sets up the logical test for morality: if you make an exception for yourself, you are being irrational and immoral.

"Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end."

The Second Formulation (Humanity). It emphasizes human dignity and rights, forbidding exploitation (like slavery or lying) where one person uses another solely for their own benefit.

Key Takeaways

Categorical = Unconditional. It applies to everyone, always. No "ifs".

Formula 1 (Universal Law): Before you act, imagine everyone else doing it. If the world breaks (logical contradiction) or you wouldn't want it (will contradiction), don't do it.

Formula 2 (Humanity): Don't use people. Treat everyone (including yourself) with respect because they are rational beings. Never just a means, always an end.

Formula 3 (Kingdom of Ends): Act like a ruler in a world where everyone is respected. Don't wait for others to be good; do your duty now.

Example: Lying promises are wrong because they can't be universalized (trust vanishes) and they treat the lender as a tool (means) to get money.

Strengths: Clear rules, protects human rights (Formula 2), fair (no exceptions).

Weaknesses: Can be inflexible (e.g., "murderer at the door" scenario), ignores consequences, clashes of duties.

All three formulations are meant to be different ways of stating the same moral principle.

Contrast with hypothetical imperatives: categorical imperatives command unconditionally, not based on any desire or goal.

The CI is derived from pure reason—it's what any rational being would recognize as duty.