Emotivism

Summary

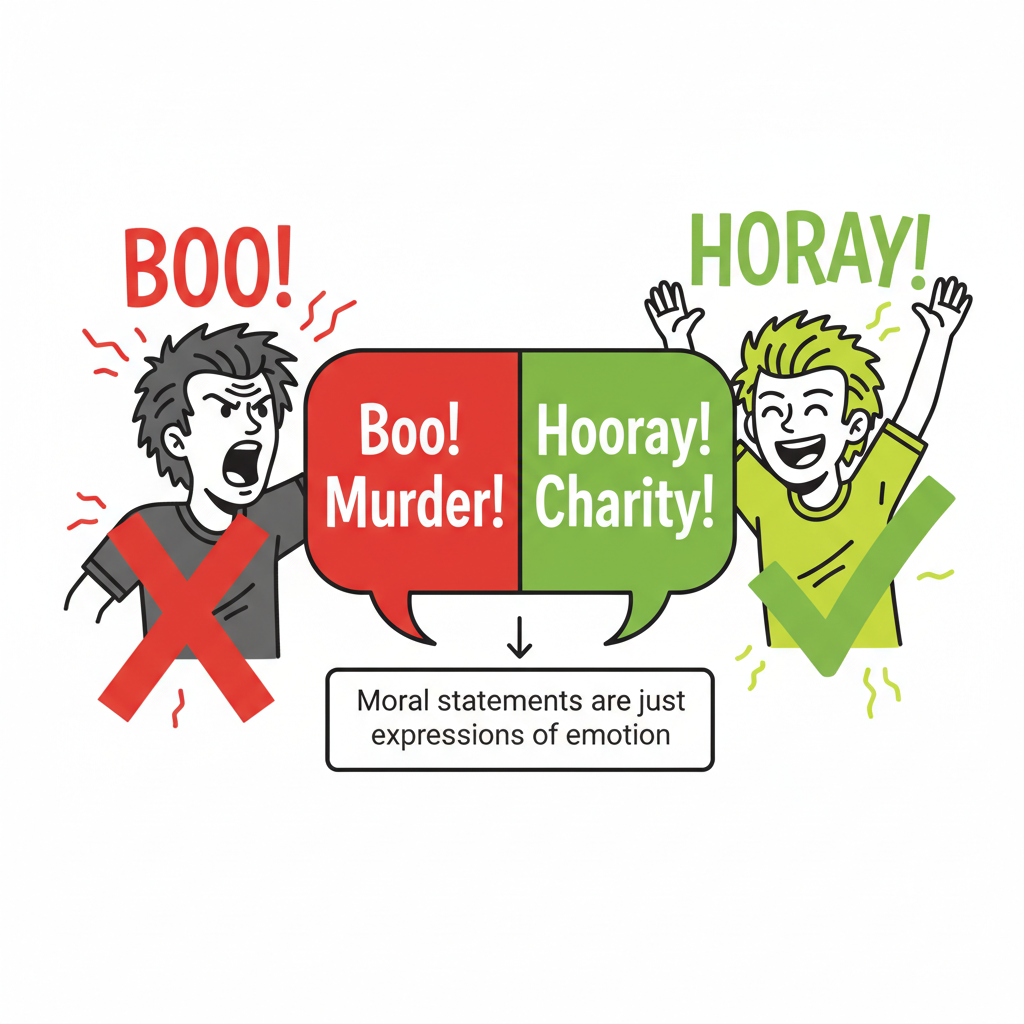

Emotivism is the meta-ethical view that moral statements don't express facts or beliefs—they express feelings of approval or disapproval. A.J. Ayer argued that saying "Murder is wrong" is just like saying "Boo! Murder!"—it's an emotional exclamation, not a factual claim. C.L. Stevenson added that moral language also commands others to share our feelings. Emotivism is non-cognitivist (moral statements aren't true/false) and anti-realist (no moral facts exist). The Frege-Geach Problem is the main criticism: if "Murder is wrong" just means "Boo! Murder!", then complex sentences like "If murder is wrong, then stealing is wrong" become nonsense because you can't have "If boo!, then...".

Detailed Explanation

What is Emotivism?

Definition

Emotivism is the view that ethical sentences do not express propositions or beliefs—they express emotions, attitudes, or feelings of approval/disapproval. When someone says "Murder is wrong," they are not stating a fact—they are expressing their personal feeling of disapproval, similar to crying out "Boo!" or "Yuck!".

1. A.J. Ayer (1910-1989)

Ayer developed emotivism based on the Verification Principle:

Verification Principle

A statement is meaningful only if it is either:

- Analytic (true by definition, e.g., "All bachelors are unmarried men"), OR

- Empirically verifiable (can be checked by observation/experience).

Moral Statements Fail the Test

- "Murder is wrong" is not analytic (it's not true by definition).

- It's not empirically verifiable—you can't see or measure "wrongness" in the world.

- Therefore, according to the Verification Principle, ethical statements are meaningless.

What They Actually Do

Instead of stating facts, moral statements express emotions:

- "Murder is wrong" = "Boo! Murder!" (expression of disapproval).

- "Charity is good" = "Hooray! Charity!" (expression of approval).

Ayer famously said:

"If I say to someone, 'You acted wrongly in stealing that money'... I am simply evincing my moral disapproval of it. It is as if I had said, 'You stole that money,' in a peculiar tone of horror".

2. C.L. Stevenson (1908-1979)

Stevenson refined Ayer's view, arguing that moral language does two things:

- Expresses emotion (like Ayer said).

- Commands or persuades others to share the same emotion.

Example

When you say "Murder is wrong," you are:

- Expressing your disapproval ("Boo! Murder!"), AND

- Trying to command others to also disapprove of murder.

Stevenson called this "persuasive definition"—using moral language to influence others' attitudes.

Emotivism vs. Other Meta-Ethical Views

Emotivism (Ayer & Stevenson)

- Non-cognitivist: Moral statements don't express beliefs; they express feelings.

- Anti-realist: No moral facts exist.

Intuitionism (Moore, Prichard, Ross)

- Cognitivist: Moral statements express beliefs.

- Realist: Moral facts exist and are known by intuition.

Naturalism (Bentham, Mill)

- Cognitivist: Moral statements express beliefs.

- Realist: Moral facts are natural facts.

Strengths of Emotivism

1. Explains Moral Disagreement

Moral disagreements are not about facts, but about clashing emotions. Explains why people get so passionate about ethical issues.

2. Explains Practical Force

Moral language is action-guiding—it tries to influence behavior. This fits how we actually use moral language (to persuade, condemn, praise).

3. Avoids Mystical Moral Facts

Doesn't require mysterious, unverifiable moral properties (like intuitionism does). Keeps ethics grounded in observable human psychology.

Weaknesses of Emotivism

1. The Frege-Geach Problem (Embedding Problem)

If "Murder is wrong" just means "Boo! Murder!", then complex sentences become nonsense.

Example:

"If murder is wrong, then you should not do it."

On emotivism, this becomes: "If boo! Murder!, then you should not do it."

This is logically incoherent—you can't have "if boo!, then...".

The Challenge: Emotivism cannot explain how moral statements function in logical arguments (conditionals, negations, disjunctions).

2. Can't Account for Moral Reasoning

If moral statements are just expressions of emotion, there is no basis for rational moral argument.

Example:

If I say "Murder is wrong" (Boo!) and you say "Murder is not wrong" (Hooray!), we are not actually disagreeing about facts—we're just expressing different emotions. There's no truth of the matter to debate.

3. Moral Statements Feel Like They Express Beliefs

Our ordinary moral language feels cognitive—we treat "Murder is wrong" as if it's true or false. Someone can say "Murder is wrong" calmly in a philosophical discussion, not expressing horror. Emotivism can't explain this.

4. Verification Principle is Self-Refuting

The Verification Principle itself is not analytic and not empirically verifiable. It's a synthetic statement about meaning, but you can't verify it empirically. Therefore, by its own standard, the Verification Principle is meaningless. This undermines the entire foundation of Ayer's emotivism.

Scholarly Perspectives

"If I say to someone, 'You acted wrongly in stealing that money'... I am simply evincing my moral disapproval of it. It is as if I had said, 'You stole that money,' in a peculiar tone of horror."

"Ethical statements are not just expressions of feeling. They also have a quasi-imperative force which is intended to change the feelings of others. When we say 'Murder is wrong' we are both expressing disapproval and commanding others to share our attitude."

Key Takeaways

- ✓Moral statements are expressions of emotion, not factual claims ("Boo! Murder!" vs. "Hooray! Charity!")

- ✓Ayer: Based on Verification Principle—moral statements are not verifiable, so they just express feelings

- ✓Stevenson: Moral language also commands/persuades others to share your emotional attitude

- ✓Non-cognitivist: Moral statements don't express beliefs or propositions

- ✓Anti-realist: No moral facts exist to be discovered

- ✓Strength: Explains moral disagreement as clashing emotions, not factual disputes

- ✓Strength: Explains why moral language is action-guiding and persuasive

- ✓Weakness: The Frege-Geach Problem—can't explain moral statements in complex logical sentences

- ✓Weakness: Can't account for rational moral reasoning and debate

- ✓Weakness: Verification Principle is self-refuting